Image-Texts 2: Taryn Simon

CIA Original Headquarters Building, Langley, Virginia”

From An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar by Taryn Simon

Via the artist's website

Last post I wrote about the Joel Sternfeld lecture at CCA, where he spoke enthusiastically about the possibilities of photographic practices that include text. I discussed his books Sweet Earth and On This Site, and then Jim Goldberg’s seminal Raised By Wolves.

Taryn Simon was another artist that Sternfeld mentioned as an example of someone who makes innovative work that incorporates text with photographs. Her output can also be considered a kind of “documentary” along with the previously discussed projects by Sternfeld and Jim Goldberg. All three artists do research and then go out into the world to gather material in the form of images and whatever information is required to produce their accompanying texts.

None is a reporter; they are poets more than direct chroniclers of any history. Of the three, Simon remains the most removed from her subjects and so may be more accurately described as an “intellectual.” She finds subjects of interest, be they, for example, the gadgets and girls of the James Bond films or the lineage of a particular set of rabbits in Australia, then meticulously collects them as photographs and organizes them into books.

An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar is one of several projects in which Simon gained impressive access in order to exhaustively compile images and information about them. Here, as it says on her website, is “an inventory of what lies hidden and out-of-view within the borders of the United States.” There are some obvious secret places, like the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters at Langley, Virginia and a nuclear waste storage facility, as well as other more surprising scenes such as a reserve for hunting exotic animals and an operating room in which a young woman is undergoing hymenoplasty. The dimensions given on Simon’s site are for large prints, but I have only seen the work online and in the book, where each page contains one image with a detailed title and a brief accompanying text, typically two paragraphs long.

The above photograph of art in the CIA headquarters lobby is unspectacular and, without the text to orient us, confusing. It is an anonymous space, mostly white aside from the pair of abstract paintings hung on perpendicular walls. Nothing we can see tells us anything about the location of the artworks, but there is a suggestion of seriousness in the ropes placed in front of them to prevent people from getting to close. It’s clearly an institutional environment of some kind, but the tight frame prevents us from gleaning any specific clues as to what it may be. The austere blankness of the space is unsettling and gives the picture a kind of dystopian science fiction vibe, common throughout this catalog of infrequently seen specimens.

The text reads:

“The Fine Arts Commission of the CIA is responsible for acquiring art to display in the Agency’s buildings. Among the Commission’s curated art are two pieces (pictured) by Thomas Downing, on long-term loan from the Vincent Melzac Collection. Downing was a member of the Washington Color School, a group of post-World War II painters whose influence helped to establish the city as a center for arts and culture. Vincent Melzac was a private collector of abstract art and the Administrative Director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.’s premier art museum.

Since its founding in 1947, the Agency has participated in both covert and public cultural diplomacy efforts throughout the world. It is speculated that some of the CIA’s involvement in the arts was designed to counter Soviet Communism by helping to popularize what it considered pro-American thought and aesthetic sensibilities. Such involvement has raised historical questions about certain art forms or styles that may have elicited the interest of the Agency, including Abstract Expressionism.”

Simon’s deft paragraphs provide enough information for us to understand what we are looking at and to infer why without directly making any particular point. The photograph can only depict surfaces—the decorated walls in the picture which are but a superficial aspect of a highly secretive organization that engages in clandestine activities all over the world and literally cannot be photographed in its entirety. The text attempts to point us toward something behind the facade, but on its own it would only be an interesting factoid, a brief speculation the likes of which have seeded many a conspiracy theory. The artwork happens at the juncture of the two combined elements, where our imagination is called into play to ponder this surface and the information at hand and to wonder what else we don’t know about the institution that it represents.

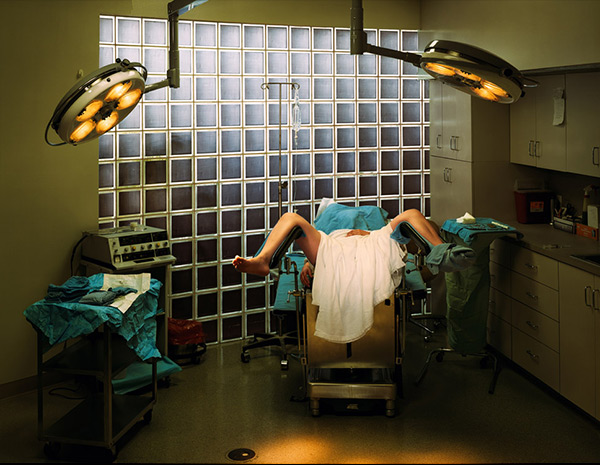

The next picture represents a more personal kind of secret than the lobby of a spy agency.

“Hymenoplasty

Cosmetic Surgery, P.A.

Fort Lauderdale, Florida”

Via the artist's website

The text explains:

“The patient in this photograph is 21 years old. She is of Palestinian descent and living in the United States. In order to adhere to cultural and familial expectations regarding her virginity and marriage, she underwent hymenoplasty. Without it she feared she would be rejected by her future husband and bring shame upon her family. She flew in secret to Florida where the operation was performed by Dr. Bernard Stern, a plastic surgeon she located on the internet.

The purpose of hymenoplasty is to reconstruct a ruptured hymen, the membrane which partially covers the opening of the vagina. It is an outpatient procedure which takes approximately 30 minutes and can be done under local or intravenous anesthesia. Dr. Stern charges $3,500 for hymenoplasty. He also performs labiaplasty and vaginal rejuvenation.”

This is a clinical photograph of a clinical approach to an intimate issue. The same uncanny quality from the CIA picture is felt here too. I think it’s the lights, which hover like UFOs over a body that we can’t see very well. From our perspective, there is barely a person to see. Her face, torso, and genitals are covered before the camera. Only her legs are fully apparent to us, and they are relatively small in the frame; the woman appears as a detail in a picture of a medical office, rather than as the subject of the photograph.

When we look closer we can see her hands and they draw us in to her. One rests on her belly, in a kind of patient gesture, and the other hangs at her side, relaxed. Or is it clinging to the table, nervous? It’s hard to say.

The picture depicts a scene that most viewers would normally not have access to, unless they are themselves surgeons or nurses. Once again, the photograph offers an opaque surface for us to examine and the written words fill in some context. We are then left to imagine what we will about the nature of the surgeon, the woman’s family, and the woman herself, as well as the broader notion that surreptitious vaginal plastic surgeries are perhaps not totally uncommon.

Simon does not write about her own opinion of the pressures this woman faces or the fact that a male doctor makes a good deal of money “fixing” women’s private parts. This is not documentary in the socially engaged vein of Jacob Riis, Michael Moore, or your favorite non-profit, driven to highlight an issue so that the audience will be moved to outrage or action over it. Rather, it is literally about the production of documents where there otherwise might not be any, or where any that do exist are not widely accessible.

Considering the work and the artist’s process in this light speaks to a fundamental facet of photography itself, as an archival process. Were there just a lens and ground glass or a viewfinder, but no mechanism through which to capture and store images, the camera would have remained a neat optical device for the scientifically inclined to take a novel gander at their surroundings. It was only with the advent of film/digital technologies and their primitive chemical precursors on tin and glass that photography became the remarkable medium that it is today.