Image-Texts: Sternfeld & Goldberg

I recently went to see Joel Sternfeld speak at California College of the Arts as part of the regular lecture series on photography that is put on there in memory of Larry Sultan.

Prior to this lecture, the only book of Sternfeld’s that I had spent significant time with was American Prospects, and that series’ distinction as a “seminal color work” (he made a joke at one point about the notion of himself and Eggleston as pioneers, circling their wagons on the frontier) kind of overshadowed my ability to clearly look at those pictures in any other light, aside from acknowledging the most obvious ironies and oddities depicted, so I appreciated hearing some of the artist’s insights into his own work, as well as the context in which that book and others were made.

I also enjoyed hearing about Sternfeld’s early experiences working in color and liked the examples from some of his early projects, which are printed in First Pictures but which I had not seen before. These included some street photographs using a flash, pictures at the beach in the summer of 1975, and a series taken at the mall, with awkward or enthusiastic shoppers sharing what they had just bought with the camera. Here appeared a glimpse of the ironic humor of American Prospects, prior to its finer formal sophistication and epic continent-wide scope.

Sternfeld spoke sincerely about some personal biographical details, such as his lifelong love of nature and interest in the seasons, which was both touching and fleshed out my understanding of his ouvre. I also really liked that he expressed an earnest appreciation for many different approaches to photography. He mentioned in positive ways both Instagram and “process based abstraction” work by artists like Sam Falls and Lucas Blalock, though he doesn’t participate in either.

What he was most enthusiastic about as a new way of working in photography was the inclusion of text along with pictures as part of a coherent, indivisible artwork, as in well-known projects by Jim Goldberg, Taryn Simon, and, more recently, Sternfeld himself.

Personal information in the talk—mostly involving closeness to or firsthand experience of violence or tragedy—that formed the foundation of Sternfeld’s analysis of his own career as perpetually interested in seeking to photograph utopian and dystopian scenarios. This binary is most apparent in the juxtaposition between Sweet Earth, which is about communes and utopian living experiments, and On This Site, a series of photographs of places around the United States where violence had occurred. Both were made around the same time and include short texts by the author that go along with each image.

He made a point of mentioning how frequently the texts are ignored by gallerists and reviewers, and he lamented the lack of critical engagement with the written components of these projects. His apparent passion for the combination of photographs with words softened somewhat my own usual urge to reject written explanations of images that I wish could stand on their own.

Certainly in some of the examples Sternfeld showed, the written component effectively impacted my reading of the images. Moreso in the pictures from On This Site, where the description of the tragedy gave the photograph a chilling resonance that might have been missing had I looked at the pictures with nothing but the ambiguous knowledge that they refer to disturbing events.[*][2]

For the examples from Sweet Earth, it was nice to have the background knowledge and Sternfeld’s writing has its own quietly humorous but still solemn poetry to it that makes it enjoyable to read, but I didn’t necessarily feel that the texts were crucial to engaging with the images. In both cases, it seemed the impetus for the inclusion of text was more a documentary, rather than artistic, motivation. This is perhaps a nuanced distinction to draw in the case of this artist, but it still matters, I think, because while the texts do have an affective resonance, they suggest that these projects are more about chronicling and conveying information than presenting poetic/artistic images whose impact on the viewer is perhaps more subtle and less concrete. In that regard they are unlike American Prospects, where the unexplained pictures point quietly at the American landscape and its inhabitants and encourage multiple readings that are intrinsically tied to the aesthetic impact of the work, which is felt on a gut level before it is logically processed.

I did not leave the lecture wholly convinced that the use of text in this way really does represent a new path forward for photographers, especially since captions are commonly incorporated into documentary projects. However, I did decide that it would be worthwhile to look through Sternfeld’s books again and to go over and write about some other work by photographers/photography artists where words and photographs are mixed together.

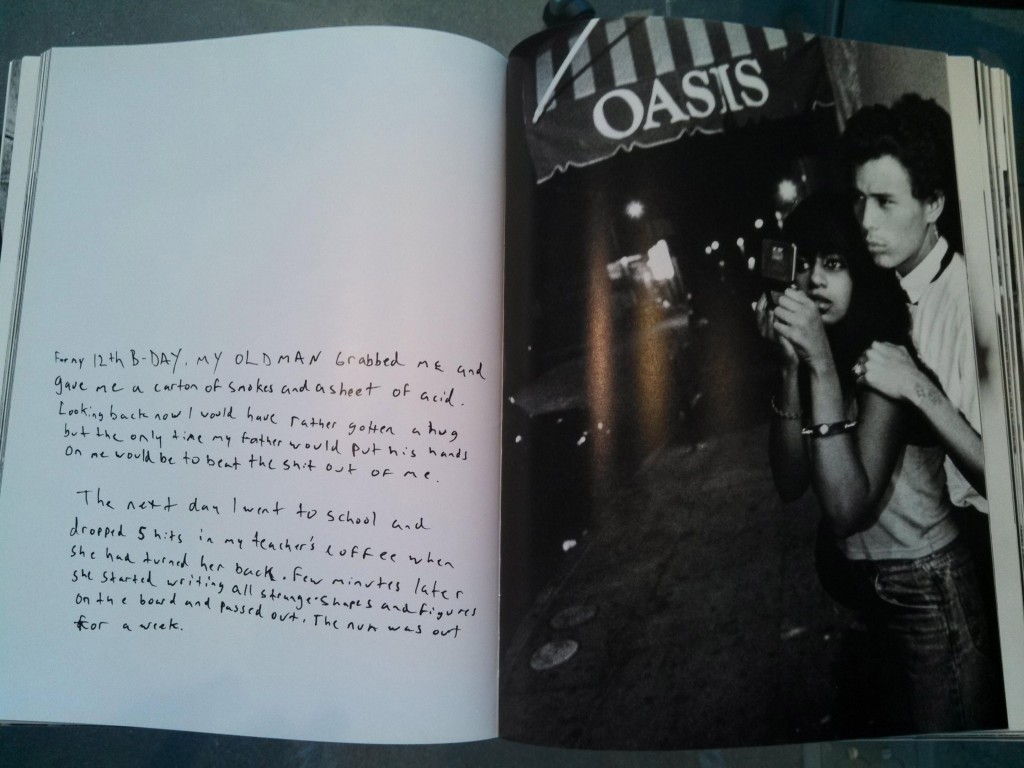

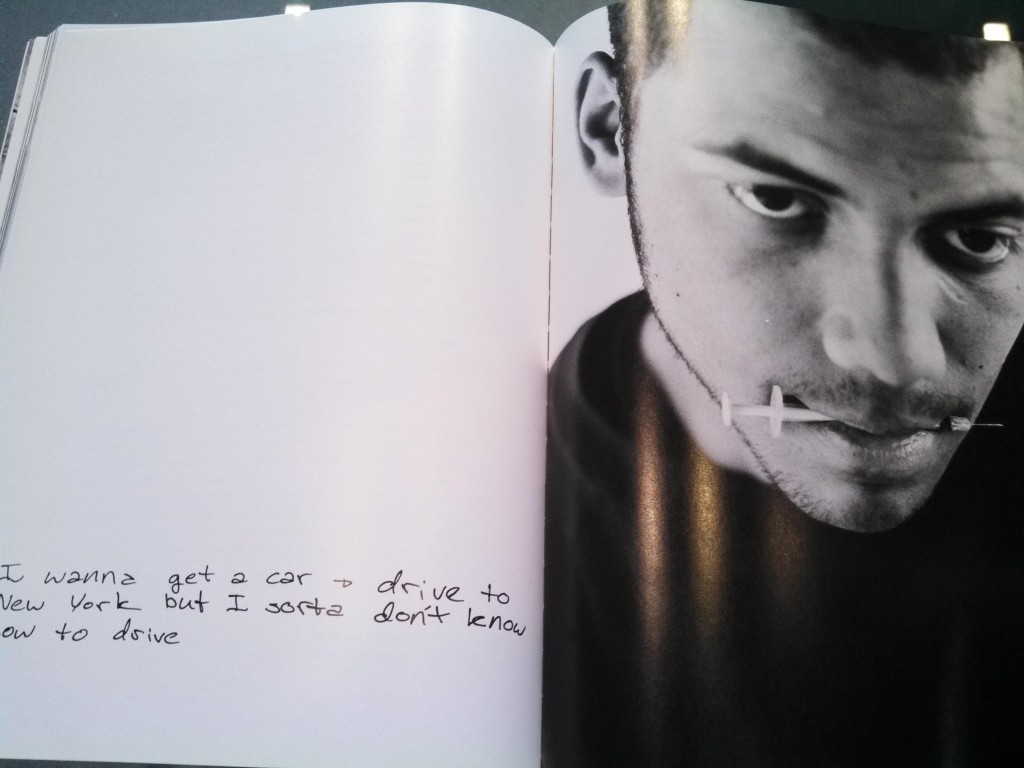

Two different kinds of texts are found in Raised By Wolves, Jim Goldberg’s book about runaways in San Francisco and Los Angeles. There are handwritten notes by the subjects of the photographs, and there are typed pages that include paragraphs from the artist’s point of view along with interviews with the young people who are his subjects and with counselors, police, and others who are familiar with the main characters. Some pages have only words and no pictures.

This is very much a documentary project, and so the use of text is consistent with the tradition of magazine stories, books, and films that include interviews, captions, voice overs, and so on, explaining the images or fleshing out the story behind them. Looking through Raised By Wolves, I find that I am drawn first to the text and then look at the pictures, so that the photographs, striking as they are, tend to feel almost like illustrations to accompany what is written in the book. Through the text I get to know the street kids that Goldberg befriends, like Echo and Tweeker Dave, and then the images confirm either my emotional sense of them or certain facts (for example, Dave has a large scar on his stomach where he claims to have been shot by his father). The pictures, as well as the handwritten notes that sometimes accompany them, feel like proof, or evidence gathered in the field that is meant to give the audience a closer, more authentic experience of what is described in the typed text throughout the book.

The text in Sweet Earth, on the other hand, gives direct background information about the photographs in the book. Each spread has a picture with text on the opposite page that tells us where the picture was taken and explains the concept of this retreat/community/institution. As he made a point of noting in his lecture, these are not objective documents that merely detail the history of each utopian experiment. They are very much written from the artist’s point of view, with a little bit of his sense of humor as well as a certain reverence for the projects described. Overall, Sternfeld seems to see his subjects as noble models for a more natural, peaceful, and spiritually fulfilling society, and he hopes to convince us of this nobility or at least acknowledge and preserve it by way of his pictures and writing. This is unlike* Raised By Wolves,* wherein Goldberg seems most focused on gathering material and understanding his subjects, not necessarily setting out his own perspective. Once again, however, there is a temptation on the part of the viewer to read first and then look, now that we know what we are being shown and why. To me, this takes some of the fun out of looking at photographs, since the most interesting or captivating aspect of a picture often stem from elements in the frame that are not readily understood. However, the text in these works is effectively employed as a kind of expository device that provides viewers with information that becomes a part of their experience of the entire work, and which is produced with as much purpose and formal awareness as the photographs themselves.

Next post I will write about two more projects in which words play a significant role among images.

*Angela Strassheim has a body of work in which she used a forensic chemical to show blood residue in domestic spaces where violent crimes took place. There the ambiguity enhances the photographs, but those are of anonymous homes rather than the historically specific locations that Sternfeld chose for his series, and traces of violence are immediately present in the frame.