Tweeting Towards Bethlehem

Twitter is the only social media platform that has held my attention since the days when I frequented topical message boards. Most of my friends in real life don’t get the appeal. But I love Twitter.

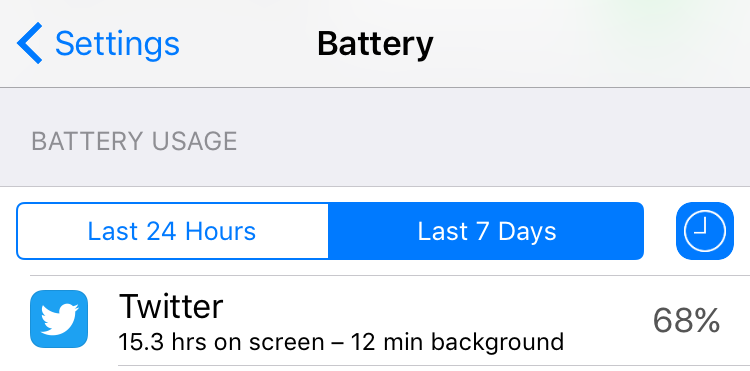

In the time that I have owned a smartphone, Twitter has been by far the single app that I have used the most. It is the primary way that I access the Internet and my almost exclusive source of news. It far outstrips any other media in terms of the number of hours I am engaged with it. I don’t regularly watch television and I can’t remember the last time I just browsed around a single website, unless I was looking for a very specific article or piece of information. During any given week, it accounts for well over 50% of the battery usage on my iPhone.

Twitter has broadened my horizons and helped me understand just how true it is that the more you know the more you know you don’t know shit. I have benefitted and grown thanks to my feed full of reporters, experts, and enthusiasts across many disciplines that have piqued my curiosity, plus some random tweeters who are just interesting or funny or worth following for some other reason of their own. I’ve been exposed to new knowledge and points of view and have encountered convincing critiques of my own beliefs, which is humbling and enlightening. It feels strange to admit it, but some of the people I found and followed have influenced my thinking perhaps as much as any reading from university, or my favorite novels.

It takes work to curate a solid feed for yourself. It is all too easy to end up in an echo chamber full of people who all think the same, or to miss out on gems simply because you do not know where to look. Getting started is daunting, and as you go along you must decide when to trim and when to cultivate heterogeneity. Branching out and learning from people in other intellectual spheres has meant exposure to, for example, NatSec wonks and international relations scholars, information security practitioners, bot and glitch art enthusiasts, and activists and reporters in the city where I live. Following a diverse feed of people who are paying close attention to issues that interest me, including people who are knowledgeable about things that I do not already understand (even when I disagree with their conclusions), is the secret sauce that makes the service truly useful.

I have few followers and it seems like Twitter-the-company doesn’t care about users like myself, who read a lot but rarely post. However, there was a point where I totally would have paid a monthly subscription fee for an improved version of Twitter – one with better tools for managing my feed and without ad network tracking and hate speech and harassment.

Sadly, it seems like the organizational strategy was to grow quickly and then IPO based on Facebook-like projections of global dominance, rather than to appreciate the potential to serve a large niche with a lovely product and run a successful business by satisfying serious users.

On Twitter the roles of broadcaster and consumer are blurred and depend more on a given user’s behavior than on a strict technical difference, as in the physical distinctions between broadcasters and viewers of television. The dark sides of this broadening have grown apparent, but I appreciate it. I get a better sense of the messy truth when I have many sources and viewpoints to juxtapose against each other. Plus, television and traditional print news rarely bring me such in depth, sustained perspectives on the issues that I am interested in.

I have learned a ton about the F-35 and military procurement from following Kelsey Atherton. The Grugq has taught me more about clandestine operations than I ever thought I would care to know. Sarah Jeong’s tweets from the courtroom were far more engaging and informative than any newspaper or TV anchor summary of the Google v. Oracle case. On the day of the coup last spring in Turkey I was reading Zeynep Tufecki tweeting from Ataturk airport, saying something’s going on but she’s not sure what, and then watched the story unfold from there.

I have also learned a tremendous amount from a technical standpoint, both about the web development work that I do professionally and about the information security topics that I follow as a related but separate interest. I am not sure how I would have otherwise been exposed to so much knowledge of subjects that I was not even aware of before.

In mobile Twitter I initially thought I had found a fantastic tool for following the news and learning new things, a replacement for a paper at breakfast or carried on my commute, but using Twitter constantly on a smartphone is really a kind of augmented reality experience. With my device in hand I am aware of the present in many places all at once. I can read about the latest election news while checking in on the progress of a protest downtown while pondering advancements in artificial intelligence and admiring the blissful contentment of a panda eating an ice pop. My brain is a spider at the center of its own web, which reels in endless morsels of information to nibble on. Or is it a trapped fly? I duck out of my surroundings into a parallel realm and it subsumes me. My sense of what’s happening is amplified to the point that Twitter can start to feel like a hallucination, a nightmare made up of gifs and hot takes and alarming observations about nuclear war.

Twitter is a remarkable platform for disseminating and gathering information, but this is not its whole purpose. It is a social network after all, with an emphasis on interactions between users. I have made a handful of acquaintances, some that I would even call friends. Sometimes I have good interactions on Twitter, but more often than not I just don’t @ people, rarely compose my own tweets, and just retweet and like things that I find interesting. I have maybe ten followers who I have interacted with directly and I like to think they appreciate my curation, but who knows. In general I think that Twitter is a bad way to have meaningful conversations with strangers. To put it mildly, 140 character broadcasts are not conducive to nuance. Even unintentionally, ambiguous comments can come across as hostile and provoke antagonistic responses. Good faith is rare and the Twittersphere is littered with dismembered straw men.

There is plenty of genuine malice too. There is a well known harassment problem on the platform that Twitter-the-company doesn’t do anything about, presumably because the metrics that measure the supposed health of their business don’t the prevalence of nastiness into account, or because the creators were so enthusiastic about free speech that they felt even the most vile commentary should be treated as equal to cat gifs and breaking news. So it is not only possible but common to be going about your business, reading regular articles and humorous quips about pop culture and current events, come upon Nazi memes and users making rape threats.

Twitter has mostly failed to prevent some users from weaponizing the platform in harassment campaigns against others. The company is weirdly incapable of developing good tools for avoiding hateful content, so it’s basically just a bizarre and terrible dimension of the user experience that millions of people put up with.

This is a realm of perpetual agitation. Everything is urgent. All sorts of jarring images and insights are jumbled together as they enter your eyes and seep into your brain. The news is disconcerting and it comes in a stream of decontextualized bleats, clamoring for your attention. This has a destabilizing effect on individuals and, apparently, on the societies that they make up together.

Twitter leadership has expressed pride in the role that the service played in movements like the Arab Spring, but they aren’t that eager to claim responsibility for the ultimately brutal outcomes of those hopeful protests in Egypt, Bahrain, and Syria. And now that we are seeing similar but distinct destabilization here in the United States, Twitter’s investors and executives are basically insulated from the impact of Web 2.0 on our collective consciousness. It seems like they cashed out years ago and are either incapable of fixing what they built or just don’t care to. They certainly built something disruptive, though.

I have gotten a lot out of Twitter. But I realize now that Twitter also takes something out of me. Consuming so much chatter makes it feel like my thoughts are no longer mine alone. In the midst of the great chorus, I sometimes forget what my own voice sounds like. The relentless onslaught of bad news fills me with despair.

I decided to take a break from Twitter for a week around the time of the RNC convention and have taken periodic days off of the service since then.

Without my feed, the world feels quiet and slow. My sense of dread is less acute without the latest hot takes reverberating through my imagination. It floats in the background, and I examine my surroundings when I need something to do with my eyes, which are less frequently fixed on my phone. I am able to place the apparent popularity of Nazi memes online into the context of the larger world, where most people are pretty normal and just want to live (without inciting a race war). I am aware that there is now a heightened chance of thermonuclear war, but no one is periodically bringing it to my immediate attention, reminding me to focus on the fact that this might happen soon but you can’t do anything about it.

I recently read The Real World of Technology, a series of lectures given by the Canadian scientist Ursula Franklin in 1989 and then updated with a few new chapters ten years later. Franklin died over the summer, and while her insights predate social media, they are prescient. I was struck by how easy it would be to continue to apply her description of the changes wrought by technologies for rapidly transmitting information (beginning with the telegraph, then on to telephones and television) to our present day Internet-oriented situation, which is often touted as totally unique and inherently more democratic and individually empowering than traditional broadcasting simply because everyone can do it themselves without the support of their own TV station.

Of mass media, Franklin writes “The images create new realities with intense emotional components. In the spectators they induce a sense of ‘being there,’ of being in some sense a participant rather than an observer. There is a powerful illusion of presence in places and on occasions where spectators, in fact, are not and have never been.” She goes on to describe how broadcast technologies encourage viewers to focus on events that are far away and that cannot be verified through personal experience, encourage the development of imaginary “pseudorealities,” and how mediated interactions lack the opportunity for “reciprocity.”

“Whenever human activities incorporate machines or rigidly prescribed procedures, the modes of human interaction change. In general, technical arrangements reduce or eliminate reciprocity. Reciprocity is some manner of interactive give and take, a genuine communication among interacting parties. For example, a face-to-face discussion or a transaction between people needs to be started , carried out, and terminated with a certain amount of reciprocity. Once technical devices are interposed, they allow a physical distance between the parties. The give and take – that is, the reciprocity – is distorted, reduced, or even eliminated.”

Unlike television, Twitter does offer a way to respond to the content that one consumes. However, more often than not this merely makes for an illusion of reciprocity, without any of the substance of genuine dialogue. It isn’t automatic like Facebook’s proprietary algorithms, but the tunability of Twitter feeds still enables users to tailor fit their own pseudoreality, which can amplify the strength and urgency of their own emotions while providing examples of the concerns of others being downplayed or outright denigrated. People with different opinions, or simply people who are different, appear much closer (and therefore maybe more threatening to small, bigoted minds), but are also more accessible to be lashed out at with little real consequence, even if the impact of online abuse can be profound and, in the case of doxing and swatting, a real part of the physical world.

The core concept of Twitter is enthralling and addictive, but no one, in designing this social network, thought to ask what kinds of social interactions are possible online, not to mention what kind of society they prefigure. In a Buzzfeed report on Twitter’s abuse problems, founder Jack Dorsey is quoted as saying that “Twitter brings you closer,” without really being able to articulate to what or why.

This closeness can exacerbate social frictions without providing an outlet for resolution. Twitter shows that the big challenge lies not in the technical problem of enabling many people to communicate with one another in real time, but in the political and cultural issues that result from difference.

Difference among humans is natural and inevitable and I am of the opinion that it can and must be channeled into the formation of a better world. However, the popularity of fascist nationalism in Europe and the United States shows that not everyone is open to this positive take. Thus, while technical problems like scaling a social network are extremely appealing to smart people in part because they entail clear, solution-oriented goals, approaches which are primarily technical will probably not resolve the issues that ail Twitter or the world at large.

Franklin makes a point of saying that it is possible to have other kinds of technologies – that this is not a choice between the alienating technologies of domination that currently structure our world and no technology at all – and she offers as a more positive example ham radio, whose operators reach out into the ether and talk to one another. I think that a comparable example on the Internet is text chat, which allows individuals in distant places to communicate in depth and over time without the preconceptions they might form about each other in person based on looks, clothes, speech, or other markers.

Though I have visited less since November, for the better part of this past year I was a heavy participant in a cyberpunk themed Slack group, set up by my now friend (once a stranger who I followed on Twitter) Sonya Mann, who wrote a blog post of her own about this community back in May.

Cyberpunk Futurism is a good place for discussion, but not a substitute for Twitter as a source of information. A lot of the time users post articles they find on Twitter or Reddit that they think the group will appreciate or that they want to discuss. It is a more intimate enclave of good will. The nature of the interactions that I have had there is encouraging to me.

Around fifteen or twenty consistent users make up the core and carry on conversations in topical channels, as well as in one general room (The Street) where all of the talk happened in the heady early days, before the conversation splintered into dozens of separate subjects. The small size of the group and the feeling of being in a more private setting rather than on the world stage of Twitter promotes greater reciprocity and a real sense of belonging among community members. We have ongoing dialogues. Some members I have gotten to know better since the group was born; others who were very active have left entirely and new people show up and integrate themselves or aren’t that engaged and disappear. There is more room for nuance and real understanding when a few people can go back and forth and fully articulate their thoughts. The fact that members recognize each other and agree to be civil and abide by Sonya’s Code of Conduct means that moderation has so far not been that big of an issue. Sometimes lines are crossed and stern words exchanged but the norms and values of the community are generally understood and followed by all.

In some ways the group is diverse and in other predictable ways it is not. Many of the users are technical to some degree, or at least well versed in the cultures of technology. Some of them I can relate to but most of their lives are quite different from mine. An embittered yet eloquent army veteran in Oklahoma, a tinkerer from Mississippi who loves mechanical keyboards, an awkward British hacker and cancer survivor. Sonya herself, the “matriarch”, whose writing I quite admire, and several others who have inspired me with their creativity and their kindness. I would not have gotten to know these people any other way, but they have made me think and I will remember them fondly.

I think it’s interesting that this social use of Slack is a mild misappropriation of the technology. Sure, something as basic as group chat can be used in many ways, but the Slack service itself is designed and marketed as a tool for work, not community building.

Dealing with difference is not a technological issue, it is a matter of people and how they understand themselves and one another. Cyberpunk Futurism gives me hope in people, that they can listen and learn and find solace and solidarity by sharing their curiosity, creativity, humor, and pain. Technology will play an important role in a better future for humans and the other species that we share this Earth with, but new tools alone will not save us. We must agree to work together.