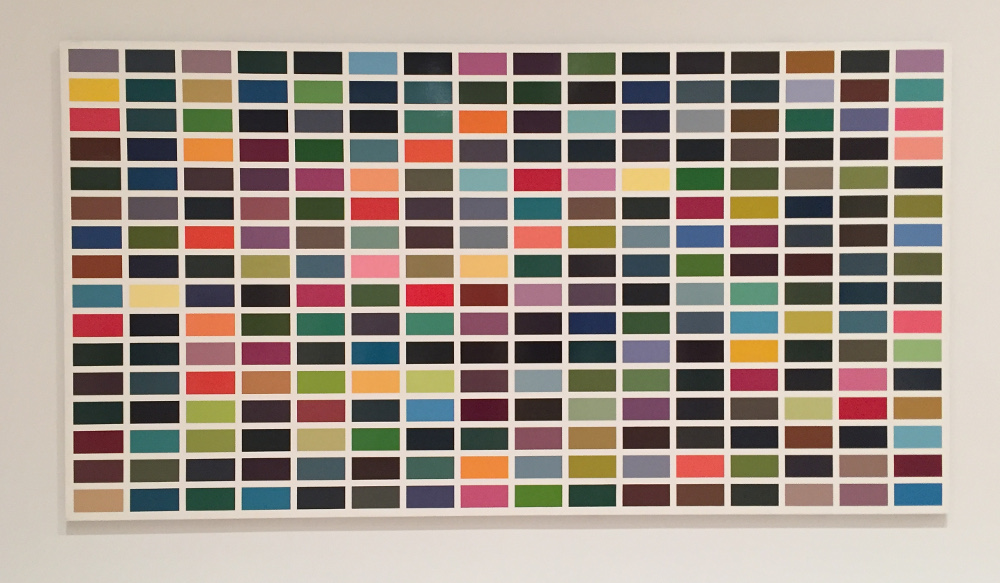

256 Colors: Gerhard Richter

I have re-visited this painting by Gerhard Richter at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art several times since I first saw it on display there a couple of months ago.

At first it is overwhelming. The surface is so large, shiny and flat that my eyes feel lost and can’t settle on any spot. They gravitate towards the corners of the colored rectangles, but their perfect points are strange to look at. It is hard to keep my gaze in one place on the painting; I keep looking around for something to focus on but can’t find it, unless I purposefully stare at one single colored square at a time. After a little while I am able to focus on distinct areas of the canvas, but my eyes still want to roam. Even though there is no scene or picture, I can eventually get lost in the grid.

The whole piece taken in at once is very attractive. The precision of the lines and the discrete blocks of color are quite satisfying to stare at. It makes me feel peaceful, looking at it. Even though the colors have been placed randomly, their absolute clarity makes the painting feel ordered and serene.

The canvas is absolutely smooth, at least from a few feet away. As though the painter wished to remove any sign of his own hand, which is interesting since that is a trope in the history of photography.

The colors all together form pleasing sequences, which I am tempted to ascribe them to the painter in order to glean some narrative, an emotional or other thrust from their placement into patterns. But they were generated using a formula and laid down by chance.

Beyond its formal attractiveness, this painting appeals to me intellectually because it was produced by way of an algorithm, but one which was executed manually by the painter instead of by a computer.

256 is a common number in computing; base-2 numbers are prevalent because ultimately, beneath many interlocking layers of abstraction, it all reduces down to binary representations of the Boolean states of bits.

Last spring I read Andrew Hodgen’s biography of Alan Turing, which covers as part of the story of one man’s life a short history of early computers and the theoretical developments in math and physics which made them possible. The thesis seems to be that the whole revolution of electronics and networks was made possible by the desperate situation of the Allied governments in World War II. At the cusp of annihilation, the British were forced to cast off assumptions of how their whole society and government operated; they had to reorganize completely in order to achieve innovations such as the breaking of the German Enigma codes. This meant allowing eccentric characters like Turing and totally out there ideas like thinking machines to become central to state run projects.

In a time of absolute crisis, imagination became more credible than in “normal” periods. People who worked in abstract fields like computability theory offered insights that were crucial to a struggle for survival. This altered rigid organizations and opened minds, so that in the ensuing years base-2 numbers could help change everything.

In this interview, Richter says that he does not believe that art has power, but that it does have the value of providing solace. He says that beauty is not in fashion now, and that it is being discredited as an ideal and misapplied to things that do not warrant the term. But a picture can be comforting simply by being beautiful.

Artists will not solve the profound crises that currently face mankind. We will not hold back rising tides or reverse environmental damage, nor will we house millions of refugees or restore malfunctioning democracy. But we can offer small respite from the psychic storms that are battering our confused society as it struggles to adapt to a different world. This is a humble, modest task, but it is an honorable one.