The Archaeologist: Alison Rossiter

I recently went to see Alison Rossiter speak at CCA. I was not familiar with her work beforehand, but she ended up giving what turned out to be one of my favorite artist talks that I have been to in a while.

She was very down to earth. She began with her own biography leading up to the work, from taking a photography class in Banff as a teenager (though she originally hails from Mississippi) through time spent studying photography at Rochester Institute of Technology and years as a young person in Montreal and New York, then on to New Jersey where, (I think) she still resides and works in a darkroom at home.

She showed some color still lifes from her time in Montreal, saying she made portraits of everything in her apartment because her French was so bad that she was afraid to go out. Then later still lifes of feminine beauty tools, pictures of horses in the New Jersey countryside, and eventually a photogram of a bottle of Windex that set the stage for her current work, which is made without a camera.

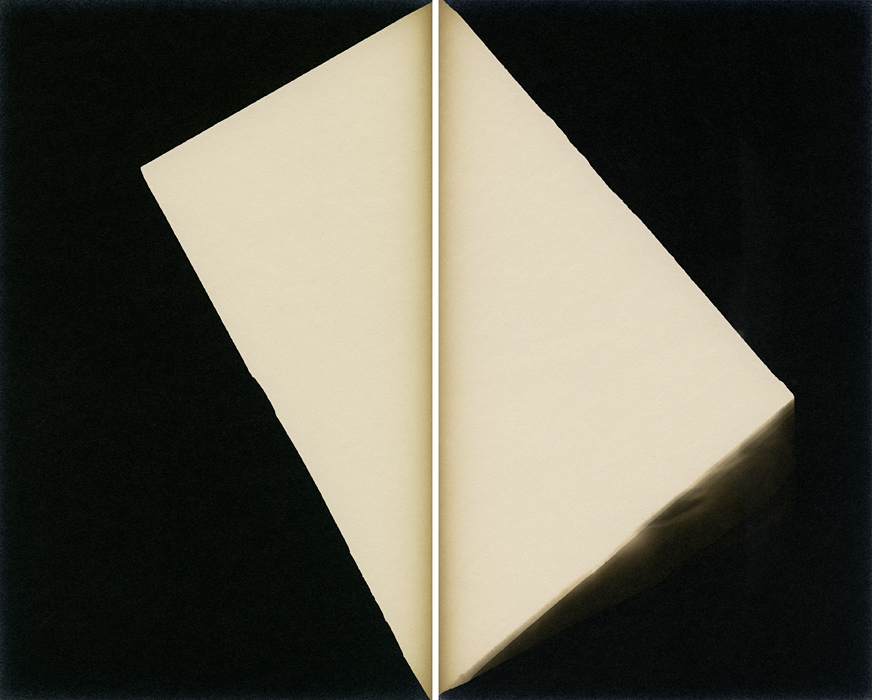

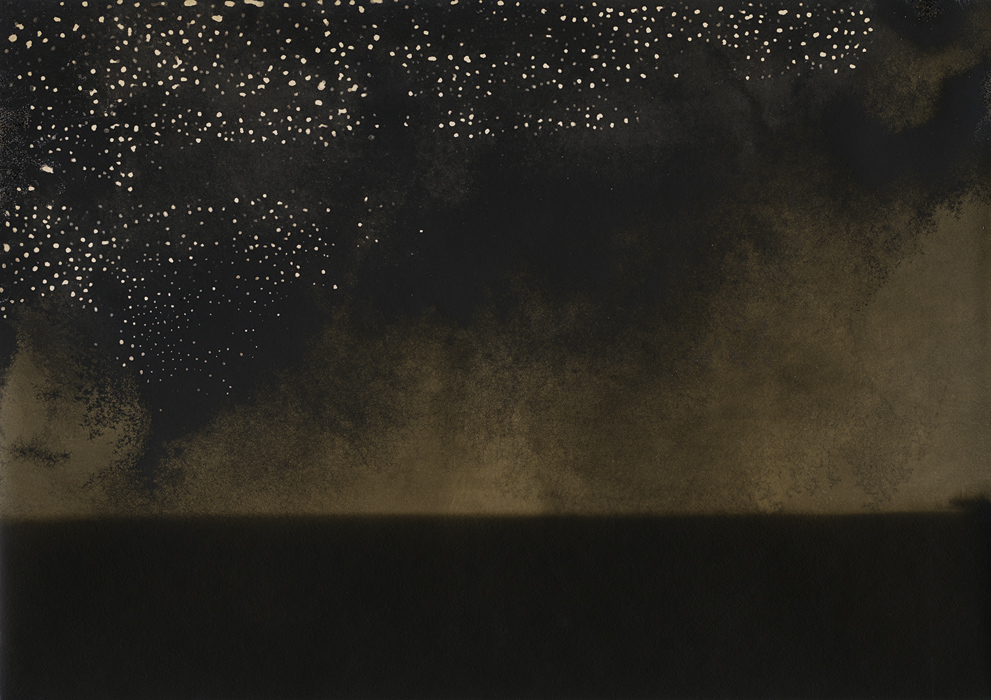

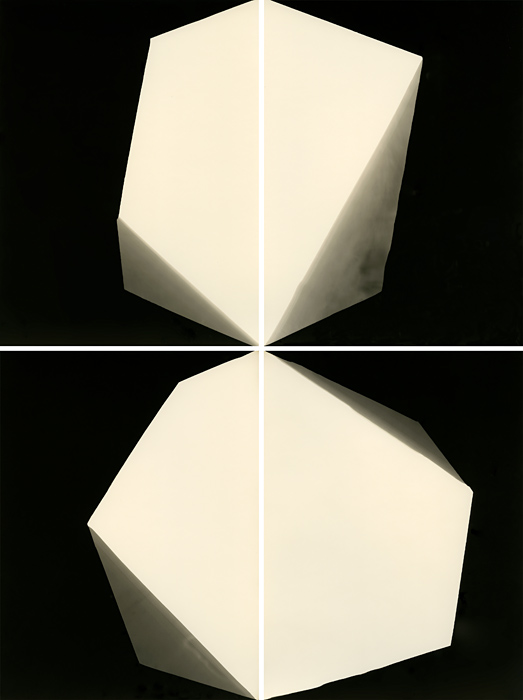

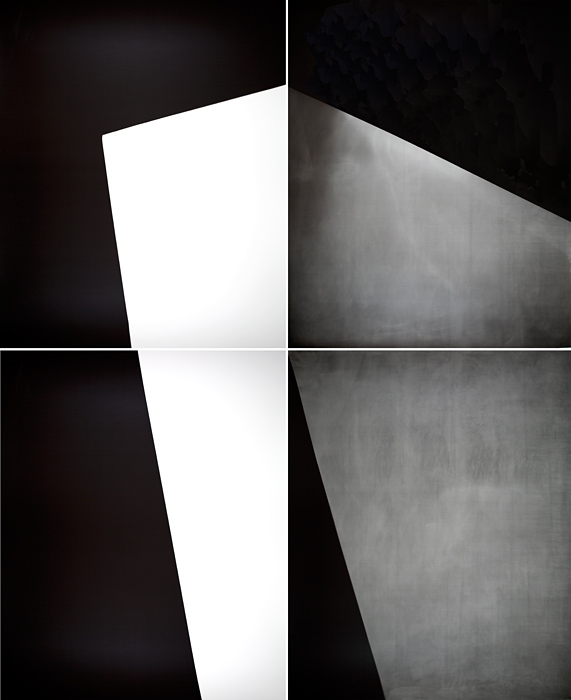

Rossiter gathers and develops expired photo paper. Sometimes she involves herself more in the result by exposing the paper, or by dipping and pouring chemicals so that some areas are developed fully before others, which allows for some fairly sophisticated tonal management in gemoetric forms. The resulting abstractions are beautiful, even eery in the way that Barnett Newman paintings can be. Oftentimes the degradation of the materials over time contributes as much to the final piece as the artist’s own hand, so collecting the paper is as important to the process as actually developing it. “Mold is my friend,” she said in reference to one heavily spotted piece.

She was technically knowledgeable about paper types and chemistry and highly aware of the history of photographic technology. She said she never had a burning desire to shoot a particular subject, but she always loved photography. Her enthusiasm for the medium and its history was apparent in the way she spoke, especially when she got into stories about particular packs of paper she had found.

Having spent a fair amount of time alone in the lab, I found it quite poignant when she spoke of the individual who left fingerprints on a piece of paper eighty years before she found it, and put it back in the box for whatever reason. That she regularly finds cut up test strips in the boxes (and sometimes uses them for her own work, though she said she has decided on a rule against cutting the paper herself) is also touching (or haunting, depending on how you think about it), a connection to someone in a similar environment but at a much different time. This all makes me think of Sans Soleil, a favorite film of mine, but I’m not sure I can organize my thoughts around that one right now.

One interesting but less immediately apparent aspect of Rossiter’s work, which is so focused on photographic antiques, is its dependence on digital technology. Because she finds a vast majority of her vintage paper stocks through eBay, it is unlikely that such a process would have been possible at all without widespread access to personal computers and the Internet. This is fascinating, and suggests that we really are only just beginning to see the impact of computing on art.

Though the images are abstract and contingent on found physical objects, this work is deeply photographic.

A lot of photography, especially in personal and documentary contexts, is concerned with preservation. This often entails a certain sensitivity to the past itself, and to the perpetual passage of time that carries us beyond every experience. Cameras promise to take images out of the present as it becomes the past and so let us supplement our own imagination with a mechanically rendered picture, a shallow substitute but somehow more sturdy than our fickle recollections. But pictures and the materials on which they are archived – be they pieces of paper or electronic drives – are also fragile, and perhaps less permanent than they seem.

Images via the website of Yossi Milo Gallery