A Visit To The Internet Archive

Earlier this month (on November 8th) I went to Aaron Swartz Day at the Internet Archive, a San Francisco-based library-like institution dedicated to preserving and enabling access to cultural artifacts in the digital era, with particular focus paid to online and other “born digital” material that may not have ever existed in true physical form.

All digital content, be it video or a page full of forum posts, is data, and data presents its own archival challenges, distinct from those entailed by the preservation of material artifacts. It is therefore no surprise that the institution involves a number of very technically-minded people, not only because of the feats of engineering required to wrangle so much data but also because makes sense that those who are intimately acquainted with how technologies work would also tend to have an acute understanding of the implications that said technologies represent for our society.

Thus, the Internet Archive’s mission, which is not so different from traditional libraries and may be described in two broad parts: the long-term preservation of digital cultures whose existence depends on certain technologies that may not be around in fifty years, let alone one hundred or thousands, and the propagation, in the present, of general access to information in the public domain.

These two purposes are referred to on the Archive’s about page as the “right to remember” and the “right to know.” That page is super interesting and includes a very articulate description of the digital library’s goals and methods, as well as several example cases of how the work done there can and has been used by others. The project aims to serve a broad public that includes professional researchers and curious laypeople; its operators understand that a democratic society functions best when it is open, since sufficient access to information is crucial to creating empowered, active citizens who are capable of participating more fully in defining the social, cultural, and political institutions in which they are enmeshed but not always necessarily represented.

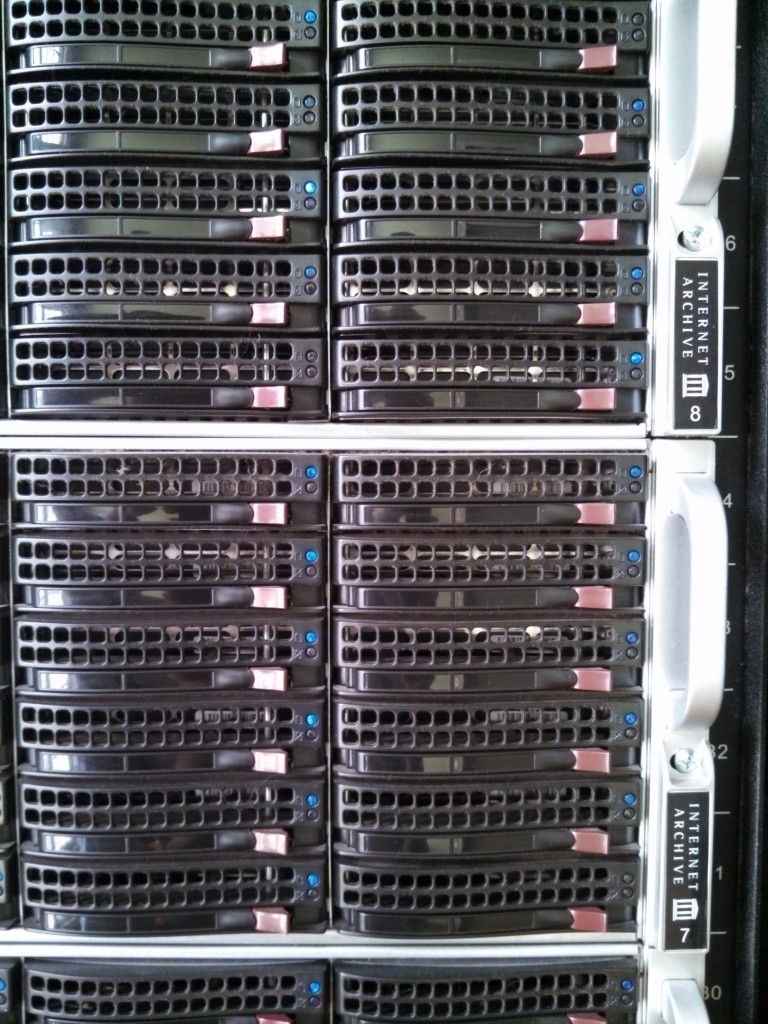

During a tour given by head librarian Brewster Kahle, I learned that there are about 9 petabytes of data in the web collection, which consists of pages that have been saved off the Internet by the Archive’s crawler programs and other crawls donated by separate organizations. There are currently around 430 billion pages available via the Wayback Machine, a basic user interface that was added to the collection in 2001 and which receives between 2000 and 3000 queries a second from the roughly 600,000 people that access it each day. Librarians around the world work on specific collections to be sure that certain subjects are archived in depth. These include collections based on subject matter, for example the Aaron Swartz collection, issues pertaining to the specific geographical locations of those librarians, and major news events. Special attention is also paid to parts of the web that go dark due to lack of financial backing, such as the US version of the Yahoo! GeoCities platform which, Wikipedia sez, held at least 38 million user-created sites before it was shut down in 2009.

There are a number of other archiving activities happening at this digital library include the collection of old films, less the Hollywood type than educational, propaganda, and so on. An effort is being made to digitize books and make them accessible online, though Kahle said that the Archive’s project is far behind that of Google, which does not allow for open access to all of the books that they have digitized. Books in the Archive’s digital collection are passed through optical character recognition systems in order to make them accessible to the blind and dyslexic. The Archive also records and stores 24 hour television broadcasts from 70 channels in 25 countries. For the time being, much of this material cannot be made available due to copyright restrictions, but commercials and American news programs can be accessed in part online, though one must borrow a DVD from the library in order to view a show in its entirety. This material is searchable by its closed captioning and OCR has also been used to make it accessible to those who cannot see or read. Efforts are being made, in collaboration with audiophile communities, to collect music, especially live concert recordings. This collection cannot be accessed fully on the web, but there is a listening station at the library and it has been made available to three computer science departments for research purposes.

On his tour, Brewster mentioned the Library of Alexandria, which he said is “best known for not being here”. Once a major center of learning for about 500 years, there are a few scraps of papyrus extant from that collection today. So, the Internet Archive makes backups around the world in order to prevent its holdings from being destroyed, on accident or by malevolent actors. Each backup center also focuses on building collections pertaining to its own geographical region.1

Kahle’s 1992 paper, “Ethics of Digital Librarianship”, available on the Archive’s website, is a worthwhile read. Thinking about his ideas against the background of current technological events, especially pertaining to surveillance and privacy in the digital realm, is illuminating. Some of what he writes about the responsibilities and pitfalls of digital librarianship resonate in thinking about what the companies that make the technology we use know about us. This comes up a lot in op-eds and the news around big players like Google, Facebook, and Twitter, but it is also relevant when thinking about smaller businesses and novel business models that depend on user data to hone their products, target ads, and find other ways to make money aside from simply selling whatever it is that they make.

Describing the ethical issues surrounding the Wide Area Information Server program, a system for querying and accessing remote repositories of information that he developed at the early supercomputer firm Thinking Machines Corporation, Kahle writes:

“The system encourages people to ask questions in natural language so that the server system can try its best to find appropriate documents. Therefore the operator of the server can collect the questions, and importantly, collect what documents the users thought were worth looking at. This combines to portray exact interests of the users. While the identity of the user is not trivial to determine since only the machine that the query came from is accessible from the server logs, as personal computers become networked, the identity of the machine will approximate the identity of the user.”

Now, working backwards through this prescient paragraph, I want to point out first that there are many places where a user’s identity on the web is directly tied to their identity in real life. I access my Google account on my cell phone and use that number for two factor authentication when I want to log in on a new machine, and the content of my emails is generally personal and frequently includes my real name. If I am logged into Chrome while browsing the web on my PC, then my browser history becomes associated with that account. Facebook and LinkedIn require that users log on as their real selves, and (FB at least, I’m not sure about the professional network) use cookies and pixel trackers to keep tabs on what users do elsewhere on the web—in order to target ads, so from a market-oriented libertarian kind of perspective one could argue that this is nothing to be concerned about, privacy-wise, because were Facebook to violate the sanctity of the data with which it has been entrusted its users would all leave and there would be no business. Though the recent revelations about an internal study that involved manipulating users’ feeds to see how their emotions were affected suggests this is not the case; some people were upset but there were no mass-defections from the network, perhaps because it already plays a massive role in the affective infrastructure of many individuals’ lives. That is, how they associate with friends and family and keep track of their own narratives and understandings of themselves.

But I am getting a little bit off track. The more important issue at hand in Brewster’s essay, which is compounded by but still overshadows the identification of users with real people, is the notion that the operator of a service which provides access to information based on users’ questions can gain access to a detailed picture of what each user’s interests are.

In the case of a physical library, “interests” might limited to just that in a simple sense: subjects which are intellectually intriguing to the user, which they would like to learn more about. For example, I need to write a paper on Herman Melville and so I have checked out some volumes of criticism that will refine my understanding of Ishmael’s relationship with Queequeg in Moby Dick.

But on the web, I might look up information about an ailment I have been experiencing and the number of a doctor who might diagnose and treat me, then watch a new trailer for a movie that I am thinking about going to see and get directions to a nearby theater where it is playing, then look up the price of some shoes I like and local retailers where I can try on a pair, then play a game, then read more about Melville to discern whether it would be worth mentioning some of his other works in my paper, then browse Twitter where I mostly click on breaking stories about government surveillance of domestic communications in the United States (but let’s not go there right now). Now a number of entities may have partial or complete information about my “interests,” which are no longer just academic, but also include my personal anxieties and desires, as well as a sense of my habits and whereabouts when I am not at my machine (and what if my machine is my phone, and I’ve been looking all of this up in between errands at the grocery store, Home Depot, and the physical library where I am going to pick up more lit-crit to be sure that my discussion of Queequeg’s tattoos takes into account all of the latest scholarship on nineteenth century sailors? What if I’ve been using Uber to travel between these places?).2

Before we get too paranoid, I must point out, as Brewster does in his paper, that collecting all of this information about what users do when they access information through computers is not strictly insidious. Ethics is not logic; these issues are subjective and complex, and everyone will benefit if we maintain a nuanced view that understands that this is a realm of trade-offs and opinions.

Brewster describes how knowing what a library patron is interested in can help librarians improve the service they provide. The same principle does apply to the Internet companies that I use to find what I’m looking for online. A well-implemented algorithm can help me come into contact with information and content that may not have otherwise reached me, faster than people thirty years ago would have imagined possible. Here, again, there is an inverse which is also true: the firm whose technology I use to navigate the vast amounts of data in the digital universe can also prevent certain sites from being seen at all. So, digital platform companies that index online data hold tremendous power both because they can tune what people find and because they know what people are accessing and how they are looking for it.

Beyond knowing what an individual is personally accessing online, massive amounts of information like this allow for modelling of human behavior with computers, so that a firm can guess things about you that you may not even know, as well as the development of artificial intelligence (which is itself the beginning of a whole other discussion of intense technological change).

The balance between the democratic empowerment represented by the ability to openly publish and access information online and the specter of surveillance by states and corporations is a pivotal issue of our age, and there is no simple way to talk about or resolve the tension. Rather, we must remain thoughtful and subtle in our positions in order to understand which trade-offs are worthwhile or necessary and which are not. Often it will be up to individuals to decide for themselves, and this depends on their being well informed. The Internet Archive, with its devotion to open access and the preservation of an electronic commons, represents a more utopian Internet politics that gives me some hope for the future of democracy in the digital world, and has left me with a lot to think about in the present.

-

1: Brewster’s mention of the Library of Alexandria reminded me of Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, in which an exchange between a tutor and his bright pupil touches on this subject and suggests sort of an opposite philosophy. After enumerating some of the treasures lost when the library burned, the student asks “How can we sleep for grief?” to which her teacher eloquently answers: “By counting our stock. Seven plays from Aeschylus, seven from Sophocles, nineteen from Euripides, my lady! You should no more grieve for the rest than for a buckle lost from your first shoe, or for your lesson book which will be lost when you are old. We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind. The procession is very long and life is very short. We die on the march. But there is nothing outside the march so nothing can be lost to it. The missing plays of Sophocles will turn up piece by piece, or be written in another language. Ancient cures for diseases will reveal themselves once more. Mathematical discoveries glimpsed and lost to view will have their time again. You do not suppose, my lady, that if all of Archimedes had been hiding in the great library of Alexandria, we would be at a loss for a corkscrew?” Stoppard’s character suggests that perhaps forgetting is not so terrible, nor is it necessarily the ultimate end of what has been (for now) forgotten. He also reminds us that what artifacts we do have were saved somewhat arbitrarily, while other equal texts were destroyed. ↩

-

2: There are ways to avoid being tracked on the web or at least limit the amount of information that is gathered on your activities/the number of entities who gather such information, but it is all about degrees of privacy/security. Ensuring complete anonymity on the web requires vigilance and breaks a lot of the functionality of many sites and web apps, and if you do go to all the lengths you can think of, nothing is perfect. I run Google Analytics on this blog because I’m curious about whether anyone is reading what I write and how the few who are end up here and so on. It’s part of the overall hobbyist activity, for me, of having a website. I won’t be upset if you’re running NoScript or Ghostery or something that prevents me from seeing data about you, since I use those things too. But not under the assumption that they are making my online activity perfectly private. ↩