At the Pier: Maurizio Anzeri

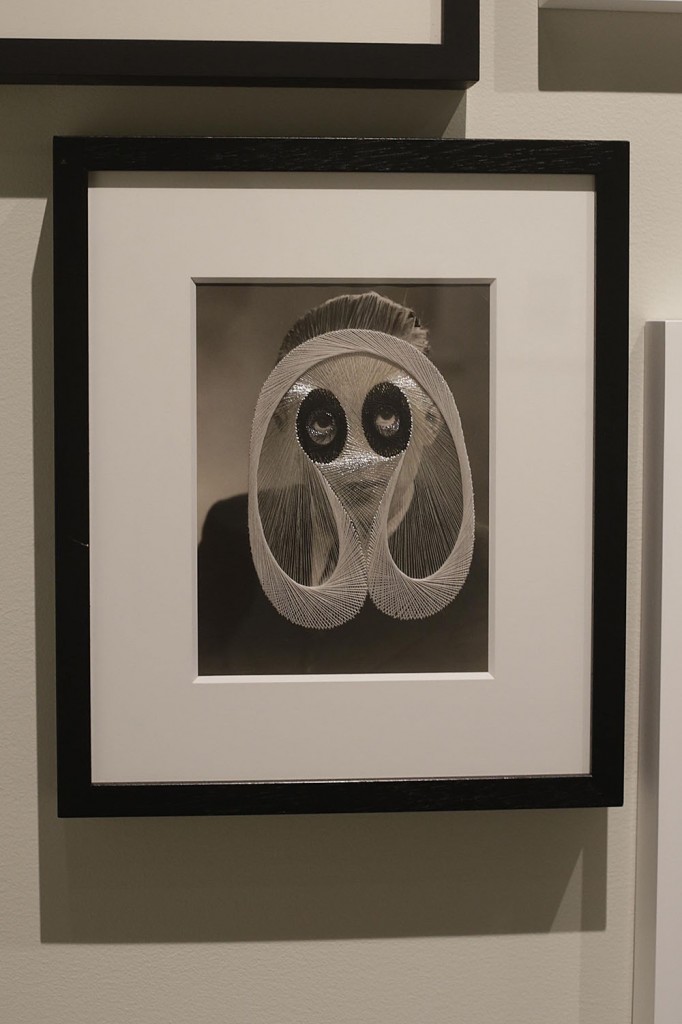

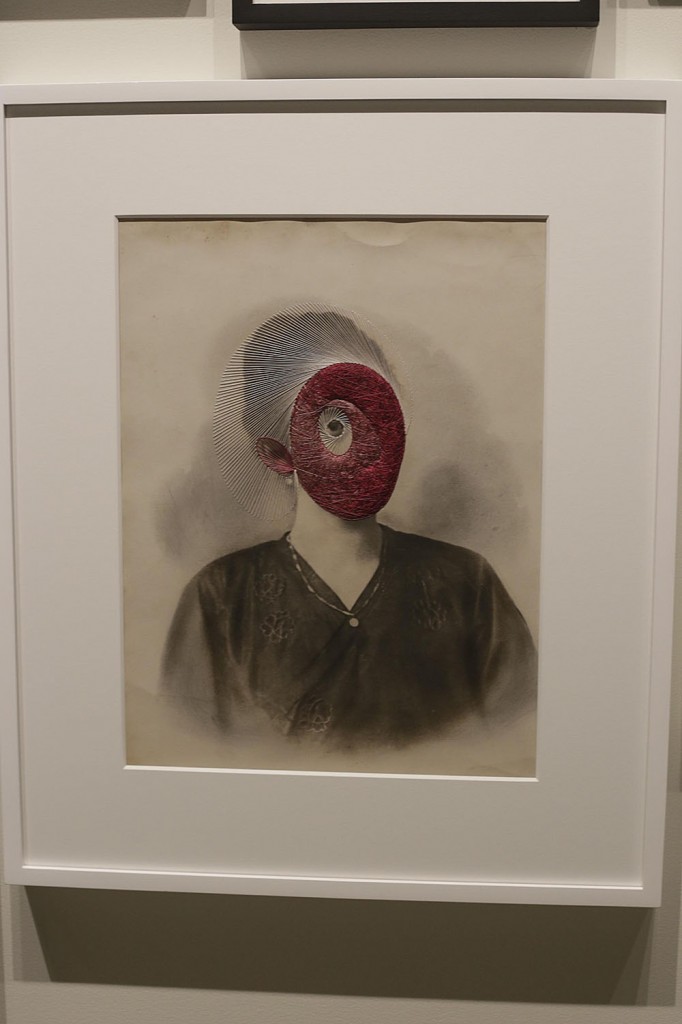

Also up at Pier 24 as part of the Secondhand show, Maurizio Anzeri’s embroidered works remind me of pictures I’ve seen of relatives or recent ancestors who were photographed in studios generations ago. For the most part these are people who died before I was born, and they are impossibly distant from the family I know today. This is partly due to the earlier technology that was used to photograph them, whose images when seen today have a connotation of being from another era. Oftentimes it seems that those pictured relatives could be anyone, much like the subjects of the prints that the artist finds and incorporates into his practice. Here, with their faces embroidered over, they look as though they decided to don masks in the studio.

Photography is an important memory technology—my dad is all about getting as much snapshot coverage as possible at family events so that he will be able to remember everything later when he is an old man—and photographs have become important documents in our own personal records of ourselves. But Anzeri’s skillful art obscures our ability to recall what has been captured in these photographs. Instead, we see unsettling impressions of human faces, suggestions of individuals overlaid with beautiful, unexpected patterns.

After looking at these pictures for a little while in the gallery I thought of a passage I quite like from The Crossing, a novel by Cormac McCarthy, one of my favorite authors:

“It was the nature of his profession that his experience with death should be greater than for most and he said that while it was true that time heals bereavement it does so only at the cost of the slow extinction of those loved ones from the heart’s memory which is the sole place of their abode then or now. Faces fade, voices dim. Seize them back, whispered the sepulturero. Speak with them. Call their names. Do this and do not let sorrow die for it is the sweetening of every gift.”

Maybe these embroidered pictures are closer than typical photographs to what actually happens in our memory over time. People and events become covered with our own remembrances over the years until what we recall is not how things were but how we have made them in the interim. Here is a semblance of someone, a scene in which we picture them in our mind’s eye (maybe from a memory, maybe inspired by a photograph) but it’s never the same to remember. A living person cannot be archived or reproduced, and yet we take pictures to try to save moments and then look at them in hopes of returning to fleeting experiences or relationships with people who are no longer present alongside us.

I would not necessarily call this work sad, but I do think that it has a sense of and respect for sorrow; I can imagine in the patient, meticulous stitching of patterns on paper that might disintegrate the moment one too many holes are poked through it a quiet acceptance of the futility of photographic memory, of the medium’s failure to preserve anything substantial at all.