At the Pier: Erik Kessels

For the last year or so I have had the opportunity to spend one day each week as a docent at Pier 24, a beautiful exhibition space in San Francisco dedicated to photography. There is about one thoughtfully curated exhibition a year, and since a new show just opened I thought I would take some time over the next few weeks or months to write down my thoughts on the pictures that are now on display.

This exhibition, entitled Secondhand, is about photographic archives and art produced using appropriated imagery. This show is particularly exciting but also challenging to write about because it is quite innovative; while it focuses on themes that have become popular in photographic art-making and which are central to understanding photography in the world today, I get the sense that most institutions would not devote this much space to such untraditional work.

As with the last show, A Sense of Place, lesser-known artists are present alongside bigger names, though there is much less space devoted to very famous pieces (by people like Jeff Wall, Andreas Gursky, or Lee Friedlander, who were up last year) than before. Some of the artists have had prior successes in the art world–I first saw Daniel Gordon’s pictures in a New Photography hang at MoMA a few years ago, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s Evidence is recognized as a groundbreaking, classic photobook, and Dive Dark, Dream Slow, a book of vernacular photographs curated by Melissa Catanese, received some recent accolades–but the subject matter here is a little bit heady and maybe not what most people would expect when visiting an art exhibit. At the same time, because much of the work is not rarified, technically dazzling Fine Art (though some of it certainly is), this show may be a lot more accessible to guests who are less bent on being shown “the best pictures” and are open to considering artwork that is more about participating in the contemporary world than producing stunning distractions from it.

The blurred distinction between curating and making art is an important part of Secondhand, whose diverse parts speak to the rich availability of captivating imagery in a world where photographs are so remarkably common that one might forget that they have been around for less than two hundred years. The included artists all draw in some way on imagery from somewhere else, be it physical found prints, magazines, or the unfathomably large pool archive which is the Internet. There are also a number of the pictures on display that are not attributed to any artist at all, as they are vernacular photographs that were collected by the Pilara Foundation for the show.

A group of installations by Erik Kessels might be called the cornerstone of the exhibition. The Dutch artist has three full rooms of work on display, and they are perhaps are the most succinct examples in the show of an artist whose mode of working is based around collection and curation, rather than the production of new imagery.

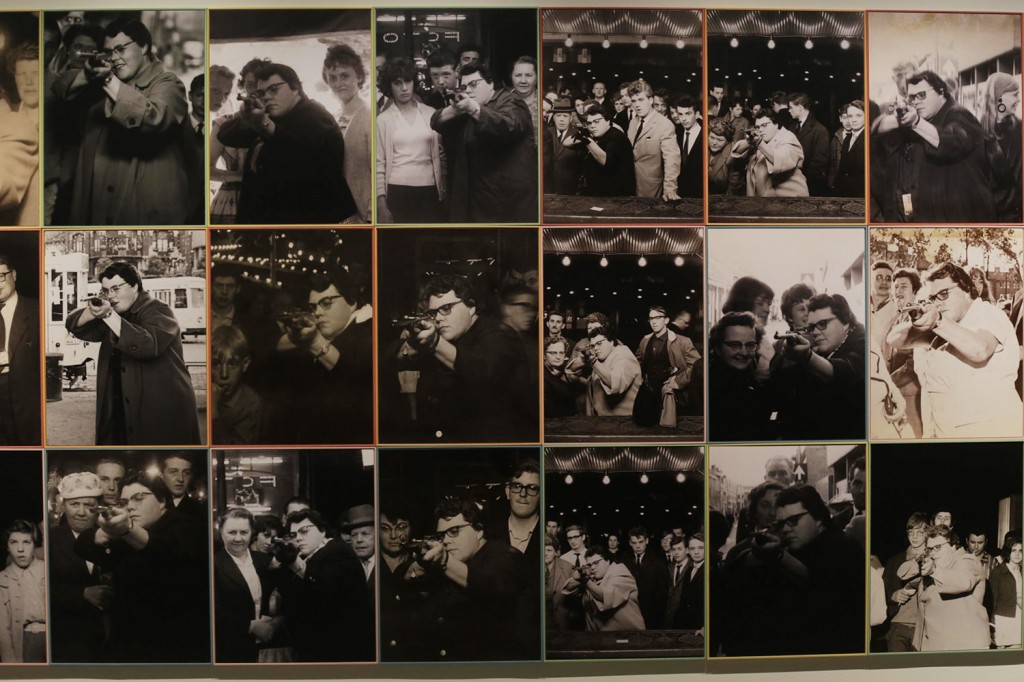

The first room contains selections from In Almost Every Picture, a series of books containing other images that Kessels collects or locates and curates. Each book is based around a repeated theme or motif or image. For example one is comprised of images from a man who has taken many pictures over the years of his wife fully clothed in different bodies of water, and another is of pictures collected from hunting forums where people post images of deer captured by remote cameras in the woods. A set of shelves on one wall hold pictures of Oolong the Bunny. I think the group that is most poignant and that feels the most complete as far as emotional resonance and intellectual food for thought are the pictures of a Dutch woman at a target shooting carnival stand wherein a successful shot triggers a camera that takes a picture of the shooter, which is then given to them to take home as their prize. Kessels has cropped the pictures so that they more closely match one another and arranged them chronologically in a close grid across one wall of a large gallery.

This wall is the easiest place for me to start to write about Kessels’ installations at the Pier, which, taken together, show an artist who is deeply interested in the way that photography is at once a vast cultural phenomenon and an intimate part of how people experience their personal lives, their relationships with others, and the world around them.

From left to right we witness a young woman growing old while also watching from a particular, limited perspective as the twentieth century passes by. Presented with such a large grid of similar images, it is daunting to try to step inside a single one. But once we do look more closely, we are rewarded with the unique details of each separate picture. Here is a television crew, here a devilish cackle on hitting the mark. She started wearing glasses quite early on, but didn’t in the very beginning. Who’s that young man holding a prize of his own? What about these other companions, later on? We invent stories in our minds about how she knows them or wonder if she does at all. Maybe some in the later photos could be her children, others might just be bystanders. The pictures themselves are different, too; the photographic technology used at the carnival stand matures along with our shooting enthusiast. A seemingly trivial souvenir becomes a poignant view of one individual’s life with the tumult of history swirling all around.

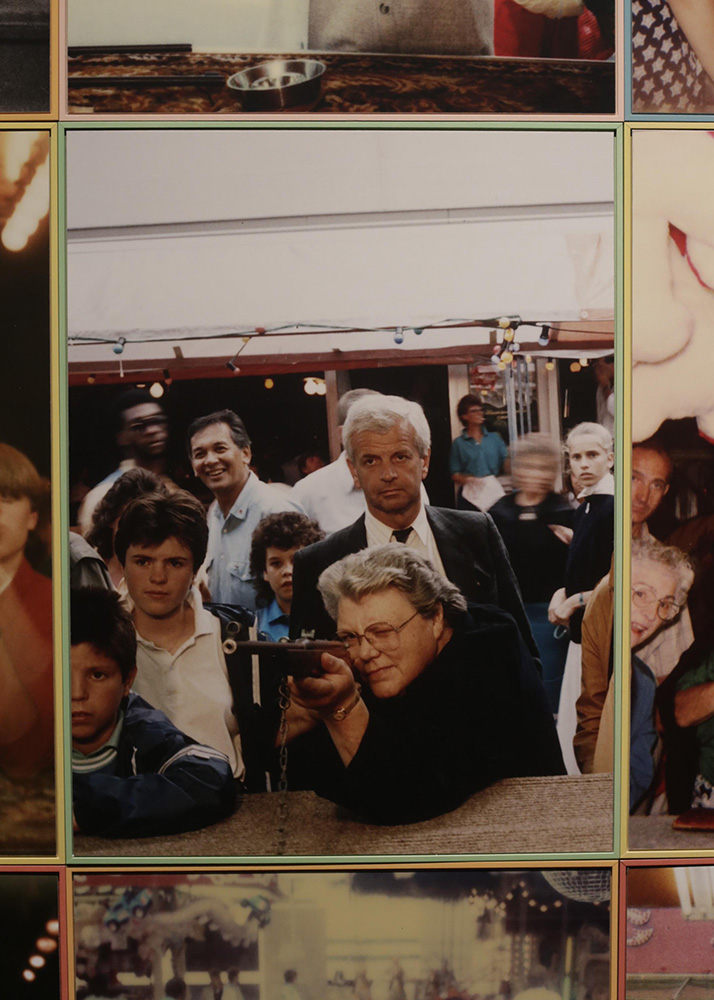

In another room, Album Beauty, Kessels has installed pages and pictures from photo albums that were collected at flea markets and other venues. Some of these are displayed oversized as wallpaper or hung in frames, others are laid out in a glass-topped case. I am not sure if it was exactly the same or a different selection, but some iteration of Album Beauty has been previously exhibited and published in a book of the same name.

I wonder about these people and how their pictures came to be here. There is a certain voyeuristic element to looking through the personal albums of strangers who probably never anticipated being seen by such a wide audience, but this is kind of in keeping with the broader photographic tradition, which has frequently involved a certain ethically ambiguous (but hopefully benign) desire to look without being seen.

I gawk at these strangers, laugh and wonder about their lives, but I also empathize with them. You have a touching smile, so sincere, and you seem like an old soul even though you’re a kid. This man looks grumpy. Are you siblings or friends? Furthermore, the ritual of photographing to commemorate events or everyday life connects me to the subjects of the pictures and to their photographers. These albums are common artifacts that also exist in my own family. My parents have pictures of me as a baby in an album somewhere, and there they are younger and the styles are different and so on. At the same time, although the individuals are anonymous, each album is unique. Some have writing, or pictures that were cut out and thoughtfully arranged together. A human being sat down and assembled all of this, and Kessels certainly wants us to consider that these are not just photographs but objects that have their own life aside from their creators and owners. Hence a whole group of pictures that have been damaged or defaced. Perhaps he also wants viewers to consider the fact that this humble art form may be dwindling now that photography has largely moved into the digital realm.

Which brings me to the final installation.

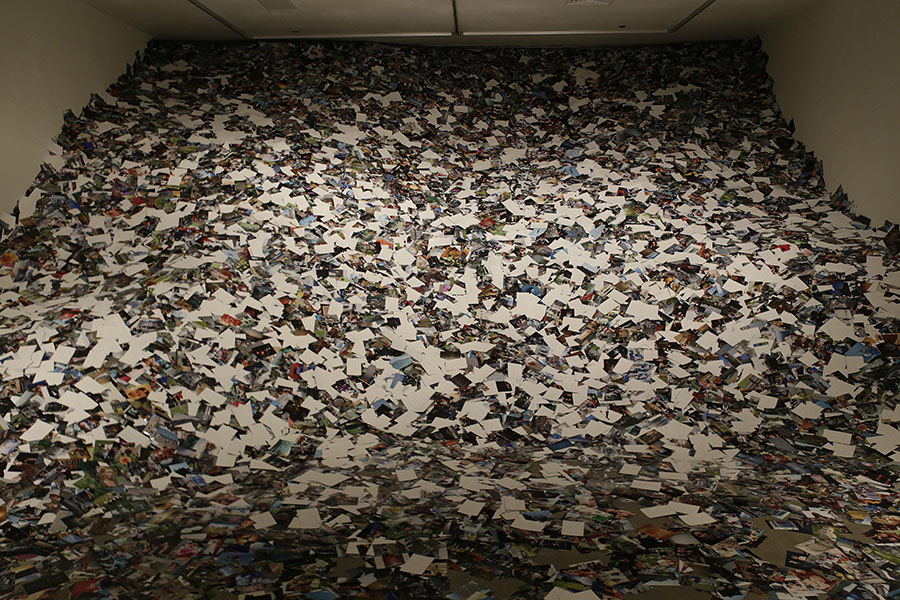

Visitors who came to the Pier during the last exhibition will recognize 24 Hours in Photos, which was left in place for a second year as it is still relevant to Secondhand. The installation consists of a room filled with small drugstore-style prints that were made from the results of a computer program being run to download every publicly visible picture uploaded to Flickr in a single 24 hour period. It is stunning to see in person and usually elicits the most immediate, enthusiastic responses from guests, who are taken aback by the giant mound of pictures and then delight in picking through them. People will often say something along the lines of “This looks like my closet!” or “Can I leave my own pictures here?” which points again to the way that Kessels’ use of popular photographic forms speaks to viewers by appealing to their own experiences as users of photographic technology.

At the same time, the piece is also a kind of bridge between the personal, physical archives of Album Beauty and the current popularity of photography in the Internet, which is itself a giant archive, albeit one that people use and experience more as a means of communication than preservation. Seeing these pictures printed out and handling them in person does make one wonder again about what is being lost in the digital ocean, where there are so many images that only complex algorithms run on powerful machines can truly sift through them all. If a photograph never exists in the physical realm, you can’t stumble upon it at a flea market, and anyway these prints are all the same, not unique like each individual object from Album Beauty.

It is tempting, then, to simply conclude that digital photography lacks the magic of its predecessor, but in reality I think that we have traded one kind of magic for another. What the Internet offers is vastness: the ability to participate in unfathomably grand dialogues, to instantaneously share images with people on the other side of the world, to click through picture after picture after picture and see almost anything. Digital photography is also more effective as an archival technology (unless the power goes out everywhere) because such images can be infinitely backed up in different places and are thus not susceptible to floods, fires, or decay in the way that albums or prints are, but these installations together do suggest that some special aspect of the medium as it was before, tucked away in books and boxes, is lost online.

All of these creative presentations of found pictures offer viewers the experience of finding some allure, be it curiosity or kinship, utter strangeness or uncanny relatability, in photographs taken by strangers who never intended for their images to be shown in the context of an art gallery (or maybe to anyone at all). Kessels’ work demonstrates the unique opportunities for communication and signification that are inherent in a medium that is an art form, a scientific instrument, and a popular tool for self-expression, identification, and memory, and prompts us to think more carefully (but not without a sense of humor) about the changing nature of photography itself.